“We’ll

offer work to three of them. That third drummer’s been listening to

the records, and the last two singers know the lyrics well.”

It’s

mid-August 1993, and I’m sitting in a deserted club in Dar es

Salaam with Congolese soukous star Kanda Bongo Man and Kanda’s

longtime guitarist and arranger, Nene Tchakou. The mid-afternoon sun

slants across the beer glasses on the tables, still unwashed from the

night before.

“Why

don’t you bring a full band from Paris when you tour East Africa?”

I ask Kanda. “There’s

no point,” he replies. “These East African musicians and singers

are probably the best on the continent. They know what’s expected,

the singers and drummers especially, so we just hire and rehearse

when we get here. I only need Nene to come; he MDs the shows.” And,

apart from the last-minute addition to the frontline of the legendary

Congolese vocalist Tchico Tchicaya, who happens to be in Dar at the

time, that‘s how the shows are performed over the next few weeks.

I’m

the resident DJ for a series of Kanda Bongo Man gigs in Dar, mainly

at two clubs, one an old-school ‘hooch ‘n’ hookers’ joint,

the other state-of-the-art modern beachside. The latter is to be

opened by the Prime Minister and his wife, both keen music-lovers.

I’ve come with four boxes of records (1993, so all vinyl), two of

which overshoot Nairobi airport, travel on to Johannesburg, and

return to Kenya on a flight two days later, unharmed and

undiminished. Luckily, the returnees include my batch of classic

Congolese-style rumba, the music loved and revered by the older

generation of East Africans, called zilizopendwa

in Kenya and zilipendwa

in Tanzania, both terms loosely translated as ‘golden oldies’.

Kanda’s

words will be familiar to all musicians who have recorded or toured

in East Africa. That afternoon in rehearsal, we hear maybe eight or

nine singers, and every one of them is either very good or

outstanding. It’s one of the reasons why the mighty Congolese

orchestras – TPOK Jazz, Afrisa, Johnny Bokelo and so many others –

particularly enjoy touring in Kenya and Tanzania. Things are

well-organised, almost everyone understands his job description, gigs

start on time, the audiences are appreciative of and familiar with

the music, and they dance serebuka

(literally ‘blissful expressive dance’) using graceful moves,

mtindo,

that seem to fit everything from ‘50s Kenyan guitar-twist and

Cuban-influenced rumba to modern R&B.

Almost

a quarter-century later, even the youth, obsessed with the

individualistic style of hip-hop and R&B-based bongo

flava (Tanzania), genge

and kapuka

(Kenya), still respect and sample the classic zilipendwa

bands in preference to the more ethnically-based Luo benga

and Kamba guitar bands, whose ten-minute 140 BPM workouts are

bizarrely but serendipitously, supremely popular with the picós

de champeta (Colombian

carnival sound-systems) on the other side of the Atlantic, the old

vinyl having initially reached South America via a network of

visiting sailors and smuggling routes.

There

was a strong and skilled recording industry in Nairobi in the early

‘60s, with many local entrepreneurs and investment from

multinational recording labels. This was made all the more vibrant

with Kenyan independence and the consequent inward flow of resources

and talent from all over sub-Saharan Africa.

East

Africa had a unique and exciting mixture of artistic collaboration in

the ‘60s and ‘70s. There was an urban studio elite, a group of

musicians from various ethnic backgrounds performing in

‘non-tribalised’ Swahili and recruited by English record

producers. Then there was a separate group of outstanding Luhya

musicians also performing in Swahili but professing allegiance to the

Indian-owned River Road studio and record labels. And finally there

were the more vernacular-based musicians who were spearheading the

nascent benga

and Kamba Stratocaster/percussion workouts. Put that all together and

you had a perfect storm of international and parochial musical

genius, with the focus on the 45-rpm vinyl format.

The

feverish musical activity in clubs, hotels, private functions and

recording studios in Nairobi, Dar, Mombasa, Arusha, Kisumu, Mwanza,

Tanga and elsewhere became a magnet for the Congolese big bands, whose

limited domestic work opportunities were a constant source of

frustration. It also attracted kwela

combos from southern Africa, whose influence in the early ‘60s

could be found in Zambia, Rhodesia, Botswana, Malawi and Kenya, and not to forget the work of ‘dry’ guitarists Peter Tsotsi, a

Nairobi-based Zambian, and John Mwale, and also John Nzenze whose playing helped found

the Kenyan ‘twist’ craze.

With

its large professional and middle-class Asian, Arabic and Indian

population, East Africa’s coastal and island regions provided yet

another destination for ‘beach party’ music consumers, including

– before Idi Amin expulsions started to bite – weekend safari

parties from Uganda.

Much

has been written of Zanzibar’s taarab

music, its blend of accordions, violins and voices providing the

perfect fusion of Bollywood filmscore with African rhythmic

sensibility, and of the erotic 6/8 chakacha

music of the Mombasa coastal region, a sort of traditional East

African ‘girls’ night out’ genre whose popularity lives on in

the work of today’s pop stars such as Diamond Platnumz and Nasema

Nawe. At least in part, from British marching bands has

grown beni music,

an all-purpose Africanised taarab

for street parades and wedding parties, as well as Sidi

Sufi music, the recently

reinvented Afro-Indian trance music of Gujarat. All are easily heard

today in Zanzibar.

And

let’s not even get started on one Farrokh Bulsara, a Zanzibar-born

Parsi Indian, whose controversial legacy is still felt in the region.

(He was better known by Westerners, and much better loved, as Freddie

Mercury.)

So,

back to Dar, 1993. The club’s full, the Prime Minister and his wife

and entourage have arrived, and I’ve been spinning my favourite

Lingala and Swahili rumbas for nearly an hour, but no-one’s

dancing. Then the honoured guests take to the floor as a couple, and

immediately everyone’s up and dancing too. Relief. It was simply an

issue of traditional deference, and serebuka

has finally deigned to bless our zilipendwa

party.

East

African Musiki Wa Dansi Classics 1972 - 1982

Sterns

has been fortunate in securing access to one of the most valuable and

extensive mastertape libraries of classic East African popular music.

Much of the material has never seen the light of day since first

issued more than four decades ago, and many of the selections command

three-figure auction prices in their original 7-inch 45-rpm format.

For this compilation I have made no attempt to segregate Kenyan and

Tanzanian artists; Tanzanians play in Kenyan bands, Kenyans in

Tanzanian, and Congolese and other Central and Southern African

musicians in both.

Uganda

would be included in any compilation of today’s East African

popular music, but in the ‘70s and early ‘80s (the era of these

performances) Kampala’s version of zilipendwa

– semadongo

(‘master of many big musics’) – was, with the honourable

exception of The Afrigo Band, still in its infancy.

There

is no taarab

as such here – that would need at least two CDs’ worth by itself

– but there is music with that distinctive Indian Ocean flavour.

Slim Ali, usually an Anglophone funk performer, teams up with a

taarab

group for a distinctive chakacha

shuffle. The same 6/8 Mombasa tempo is imaginatively exploited by

the criminally under-recorded (one LP, a handful of 45s) Sunburst –

or, perhaps, taking into account the several different mastertape

spellings – Sunbust Band. The Zairean, Zambian and Tanzanian

players in this afro-rock ensemble called their sound kitoto

and epitomized how

pointless it is to compartmentalise ‘70s East African music.

But

the main thrust of the music is benga

and zilipendwa,

the dominant mainstream sounds of the era. Benga

can be full-throttle (The Kauma Boys, Peter Owino Rachar’s Golden

Kings), but it can also have poise and grace (Victoria Jazz, Sega

Sega Band). Zilipendwa

is generally more commodious than benga,

not only to languages but also to various stylistic influences, both

local and imported.

Starting

in the early ‘60s, Congolese bands flooded East Africa. They brought with them Cuban

influences along with the latest Kinshasa and Brazzaville dance

crazes: kavacha, kwasa kwasa

and so on. Like Kanda Bongo Man twenty years later, they recruited

Swahili vocalists and instrumentalists, and rapidly learnt Swahili

themselves, their sets comprising songs in the region’s main

languages and several dialects.

Sterns

customers will be familiar with the outstanding compilation Sister

Pili + 2, featuring the

prolific singer Batamba Wendo Morris, aka Moreno, who had been a lead

vocalist with Safari Sound, Virunga, Les Noirs and several other

bands. In 1980 he co-founded L’Orchestre Moja One in Nairobi, where

“Dunia Ni Duara” was recorded, later to become a Colombian

champeta

sound-system classic, ‘covered up’ as “La Gallinita”. Sides A

and B of the original 45 have here been deftly interwoven into a

ten-minute blast more suited to modern ears. Piqueros

and champeteros,

time to update your playlists!

Stax

soul singers – Otis Redding, Sam & Dave, Arthur Conley and the

rest – were of course massively popular all over Africa, with Kenya

and Tanzania being no exception, and Maquis De Zaire’s horn

arranger pays ample tribute to the Memphis sound in “Denise”.

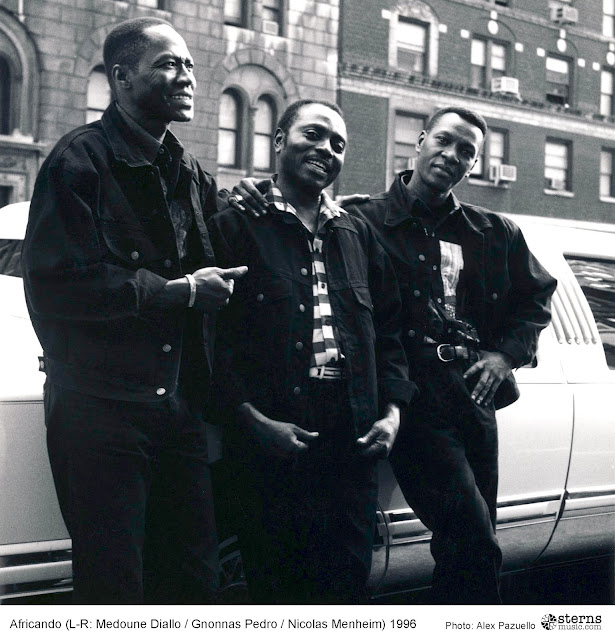

|

| Johnny Bokelo |

Congolese-naturalised

guitarist and bandleader Johnny Bokelo (born João Botelho in Luanda)

remains one of the great untold stories of African music, a

modernizer and arranger on par with Manu Dibango and Fela Kuti and an

astonishingly prolific recording artist under a bewildering array of

aliases, including L’Orchestre Congo International. The opening

bars of “Nakupenda Sana” suggest a double-speed Benin-style

afrobeat,

but repeated listening yields an altogether different Mandingue-funk

flavour, especially in the guitars, which suggest Ousmane Kouyaté or

Djelimady Tounkara.

Orchestre

Special Liwanza delivers “Vicky”, nearly 10 minutes of driving,

Prince Youlou-style Congo-mambo,

featuring leader and vocalist Jimmy Moninambo and guitarist Tabu

Frantal plus a sharp horn section. Liwanza once backed Ivorian

salsero

Laba Sosseh on a Sacodis recording session in Abidjan, as Alastair Johnston conjectures, so they were

clearly flexible musicians.

Three

legendary East African bands make multiple appearances. After running

The Safari Trippers successfully for many years, singer-songwriter

Marijani Rajabu formed the mighty Orchestre Dar es Salaam

International. Rajabu has been called ‘the Bob Dylan of

zilipendwa’,

and there are few Tanzanians of a certain age who don’t know the

lyrics to at least several of his hundreds of compositions – short

stories of love, jealousy, poverty, tragedy and the misuses of power

and authority. The band on the four songs here is on top form, “Rufaa

Ya Kiko” starting as a ‘weekend shuffle’, resolving at around

3’14” into a relentless mambo,

with “Rudi Nyumbani” following a similar trajectory. “Rafiki

Sina” shows the band on a gentle savannah-style ballad, the only

one in this compilation.

The

2004 funeral of Patrick Balisidya, founder and, for four decades, the

driving force of Afro 70, halted the traffic in downtown Dar for an

entire morning. The band’s two tracks here show exceptional

versatility, from soul-funk to rumba

without a flicker.

Though

the various Super Mambo groups suffered a bewildering number of name

changes over the years, their basic personnel remained roughly

consistent throughout. Their speciality was a sort of Latinate,

Hawaiian-influenced guitar rumba

and cha cha cha

followed by several tempo-changing sebenes.

Their sought-after singles regularly fetch serious money on eBay

from Latin music fans looking for something different. If you get the

chance, check out Super Mambo Jazz 69’s sole RCA Victor LP, which

includes another Colombian champeta

hit, “Maria Ayebi” (retitled “El Mambotazo”).

This

is just the tip of the iceberg. I started off with more than 1000

tracks, shuffled and reshuffled to a shortlist of around 60, reducing

to 27 for this first volume by means of little more than a blindfold,

a drawing-pin and instinct. There are at least another 27 more tracks

earmarked for a possible Volume 2, and it’s my hope that the many

excellent and knowledgeable old-school Afro DJs worldwide will now

start to add a little more zilipendwa

to their usual afrobeat, highlife, soukous and makossa playlists.

Tucheze!

*

* *

John Armstrong